DAMAGE OVER TIME, OVER TIME

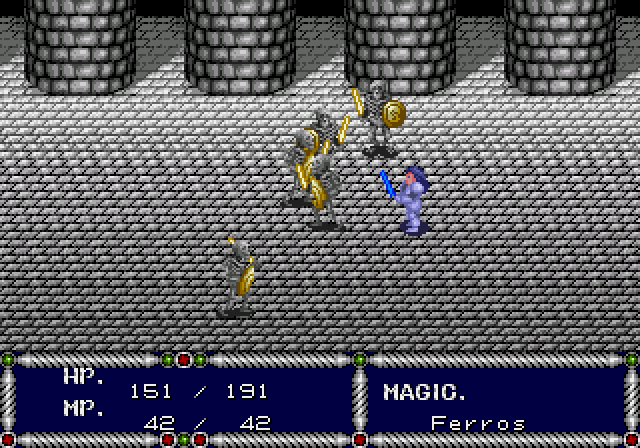

Poison's neverending menace in Sword of Vermilion

I played Sword of Vermilion (1989) in May and was surprised how much it asked me to think about poison. It shouldn't be so unusual: Poison, as a status affliction that depletes your health over time, is extremely common in RPGs. It's the archetypal "status ailment", and its damage-per-step form goes back at least as far as Wizardry (1981). But despite its prevalence, poison is rarely a site of deep interaction during play. When I think about dealing with poison, what comes to mind is reflexively opening the menu to quaff one of my 99 antidotes or cast a cheap remedy spell before moving on without a second thought. On twitter I joked that every RPG has a point where poison becomes irrelevant, but in Sword of Vermilion that point never came. In fact, not only did poison management persist as an essential strategic consideration from early in the game until the very end, but my relationship to it continued to evolve as I gained new tools and had to renegotiate my approach to poison control.

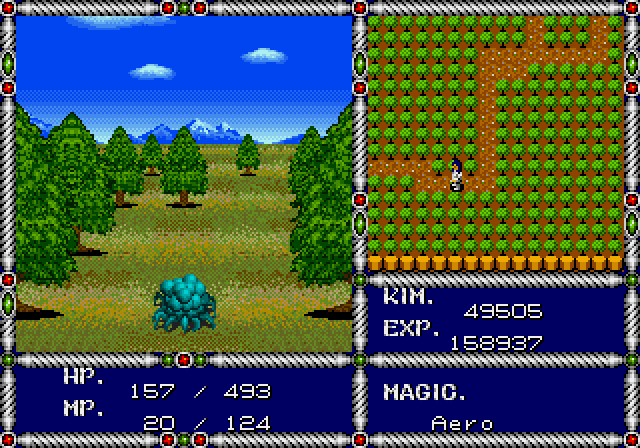

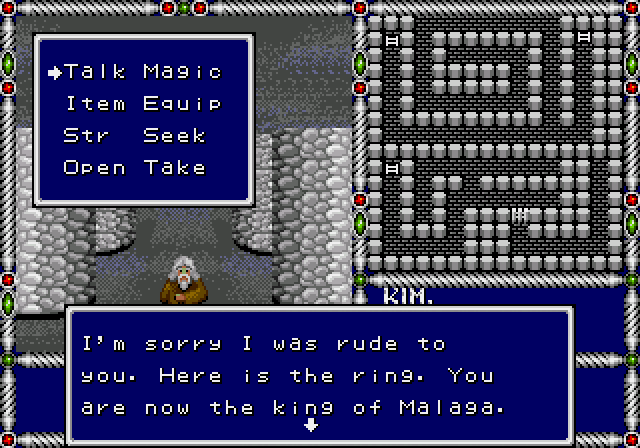

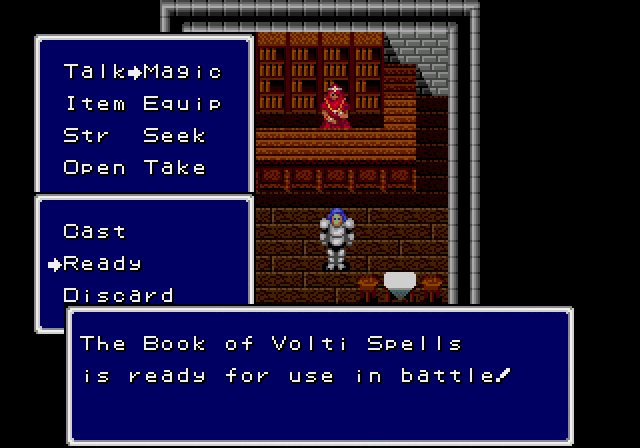

Sword of Vermilion was a fairly traditional JRPG in the lineage of Dragon Quest, with a conventional play structure centered on managing resources as I stocked up in town, trekked across the overworld, dove into dungeons, and fended off random encounters all the while. Vermilion distinguished itself visually by its dual-view map navigation and two separate real-time combat systems, but the gameplay found its identity in its sense of challenge, its systems carefully calibrated to draw the maximum drama out of its concise palette. At the crux of this balance was a tight economy of resources, constrained not only by gold and mana but also by strict limits on how many items, spells, and equipment pieces I could carry, with a hard cap of 8 articles on each. With such limits in place, a full arsenal of healing potions and magic was maybe good for two to four full HP recoveries per outing: a paltry amount in most RPGs, just enough to get by in this one, and never enough to let me relax. Moreover, finite carrying capacity motivated a mindset of preparing for the dangers of the dungeon in advance, anticipating what troubles I might run into and allocating my precious few slots accordingly. With the margins of error so slim, survival turned on the quality of my preparation just as much as my resource and risk management in the field.

With barely enough resources at my disposal to sustain me in the first place, the threat of poison carried significant weight. Sword of Vermilion’s strict resource economy was thus the backbone of my intimate relationship with poison. Yet the backbone is not the whole body. To fully account for the length, complexity, and variability of my relationship with poison, I’ve identified three specific factors in Sword of Vermilion’s design, which represent consequences and extensions of the game’s philosophy of scarcity:

- First, by establishing poison as a critical and commonplace threat, Sword of Vermilion persuaded me to make specific and ongoing preparations to counter it.

- Second, by placing poison management in competition with my other survival needs, Sword of Vermilion encouraged me to prepare for poison as efficiently as I could to free up resources for other concerns.

- Finally, by regularly varying conditions between scenarios, Sword of Vermilion subjected the most efficient preparation, and by extension my own strategy, to constant flux.

The cumulative effect of these phenomena was to promote a relationship of continual reevaluation of my poison management strategy, in which I was constantly anticipating run-ins with poison and monitoring whether my preparations were appropriate. I’ll describe each phenomenon in greater detail in the following section.

The necessity of preparation

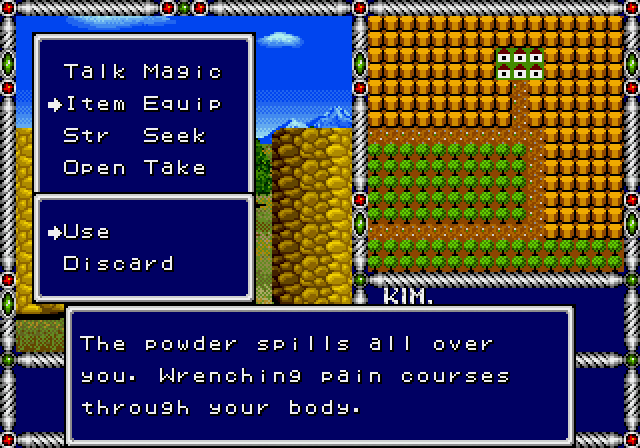

Getting poisoned even once posed a serious threat to my survival, and for that reason it was necessary to prepared to response to it. How was poison so dangerous? By my estimate, it dealt between 0.5 and 1% of my max HP in damage per step—not exactly a terrifying figure. But the danger of poison was a function not only of its potency but also of the length of time spent in the field and, crucially, the availability of healing resources. With the average dungeon excursion running (say) between 500 and 1000 steps, and my combined item and magic pools refilling my max HP a couple times over, a single poisoning early in an adventure had the potential to deplete my entire healing reserves on its own. Because poison had the potential to inflict more damage than I could practically offset with conventional healing, it represented a qualitatively different threat than conventional damage, and so required me to stock specific remedies for it, like consumable Poison Balms or the reusable Toxios spell. It could take dozens of Herbs to do the work of one Poison Balm, and I could only carry 8.

The danger of poison also depended on the likelihood of getting poisoned, and in Sword of Vermilion, getting poisoned was a fact of life. Of course poison was more prevalent in some areas than others, but almost everywhere there was at least one venomous enemy to watch out for, and one hit was all it took to infect me, so I could always count on poison to rear its ugly head. Inevitability made preparation a constant, proactive affair. Gearing up for a new area, I couldn’t wait until I knew poison was present there before I decided to prepare for it. It made far more sense to assume that it would be, and devote some resources to poison management in anticipation. In this way, Sword of Vermilion kept me thinking about poison even when it was off-screen. Together, the severity and pervasiveness of the threat exerted a pressure to make specific and systematic poison preparations.

The cost of preparation

Poison preparedness always came at a tangible price. Gold and MP were important resources, but the real currency of poison preparedness was opportunity cost: Every remedy I could stock competed for a spot in one of my inventories with something else I needed. Poison Balms fought with healing potions, light sources, and warp items for my 8 item slots; Toxios competed with a host of other powerful utility spells for its spellbook slot; and the Poison Shield, which conferred blanket immunity to poison, vied with stronger shields for my left hand. The tenseness of these tradeoffs followed directly from Sword of Vermilion’s philosophy of never giving me all the resources I needed to feel secure on every front at once, and the result was that all my needs competed with each other for the same resources. To ensure that all my needs were met, it was in my interest to make my poison management strategy as lean as possible, so that excess resources could be made available for other survival concerns. In this way, poison management demanded not just the passive commitment of doing it, but the active engagement of doing it as efficiently as I could.

The evolution of preparation

Efficiency itself was not a static goal, but one that changed shape from scenario to scenario. This was important: If a recurring tension neatly resolves the same way every time, then on the scale of multiple events, that tension is effectively nullified. By regularly changing the variables in the equation of poison management, Sword of Vermilion precluded any one solution from being the best in every situation, keeping the tension of poison alive even as my power to manage it grew. Regular disturbances in the poison landscape compelled me to constantly reassess how well my habitual strategies were working, and when I sensed they might not be working well enough, to change them.

The efficiency of a poison management strategy depends on both the danger posed by poison and the means for combating it, and both of these were in flux. The danger of poison, and hence the ideal preparations, differed in degree from place to place, depending on the prevalence of venomous enemies, how safely each type could be routed or fled, and the length of time my objective required me to spend in hostile territory. These are all factors that are difficult to account for, so they rarely influenced my preparations, but variations in them nevertheless affected the way those preparations played out.

Varying the means of poison management means that at different times, different tools were available or had different costs. Poison Balms were in stores early on, Toxios appeared about halfway through the game, and I picked up the Poison Shield around the two-thirds mark. Each new tool solved the same problem at a price that was generally lower, but qualitatively different. Toxios was a welcome acquisition because I had been straining under the constant commitment of two or three item slots to Poison Balms. When Toxios offered to let me fill those slots with much needed Medicine at the expense of a surplus spellbook slot, the terms of the tradeoff were immediately clear and personally relevant. They responded to the specific relationship I had already formed with poison management, and added a new dimension to it by asking me to consider an altogether new form it could take on—stronger, but reshaped. The most important effect of receiving these upgrades wasn’t the outcome but the process of reflection itself, which continued well beyond first committing to Toxios. It continued when I bought new magicks and foresaw the future-tense need to downsize my inventory to make room for new spells; it continued when I obtained the Poison Shield and sold Toxios to make room for another spellbook; and it continued whenever I found a new shield and ruminated on whether its defense rating was high enough to warrant replacing my Poison Shield and buying back Toxios. As each tool waxed and waned in opportunity cost, it prompted me to reevaluate my poison management strategy over and over again to best keep up with the stringent demands of dungeon-crawling.

Continuous reevaluation encapsulates what it means to have an enduring and intentional relationship with poison. The question of poison management held my attention all throughout the game largely because my survival depended on my answer being good enough, and the quality of a given answer changed with every new scenario. It was not necessarily a difficult question. It was easy to understand and in fact somewhat subjective, with a margin of error wide enough to admit imperfect answers. I just had to pay attention to what was going on and make sure my habits still made sense in the current moment. Hence, continuous reevaluation. Of course, maintaining this environment took the authors some work: in this case, it took poison seriously threatening a web of conflicting survival needs that competed for scarce resources in an ever-changing ecosystem for the entire game. Their success can only be the result of competent system design and RPG balance working in concert—Sword of Vermilion’s forte.

Put a little differently, poison’s command of my attention is a question of engagement. How do we design and balance RPGs to hold our attention, to make us curious about rules of the world and invested in understanding them better, and to promote interactions with systems that are proactive and intentional rather than passive and automatic? I hesitate to generalize too much from the observations I’ve laid out—they’re descriptions, not prescriptions. Yet there’s nothing unique about poison among other concerns. If I look back on my time with Sword of Vermilion, there’s little I’ve said about poison management that isn’t also true of my relationships with conventional healing or offensive magic selection, both of which garnered conscious and inquisitive attention from me throughout the whole game. I can only speak for myself, but when I play games about interacting with systems, I want those systems to engage me fully. Poison is one systemic storytelling device I’ve seen people bemoan as shallow, uninteresting, outdated—signs that it isn’t a site of meaningful engagement for them. Understanding how Sword of Vermilion was able to make poison one, even if just for me, may shed some light on how future games can shape meaningful experiences around poison, or status ailments, or other systemic storytelling devices in the RPG toolbox.

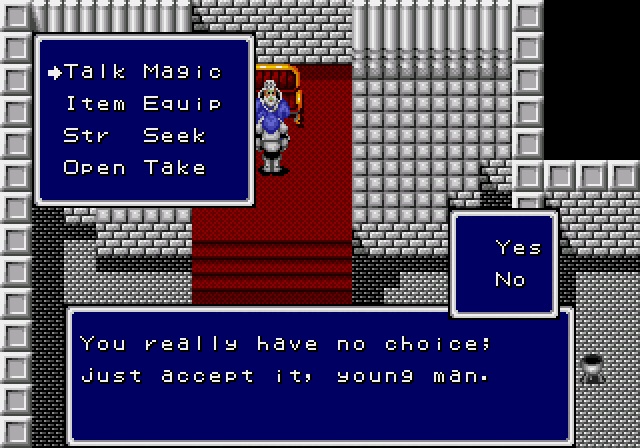

At the end of the game, right before the final dungeon, there was a scenario where I was afflicted with an incurable poison. It was quantitatively no stronger than regular poison, but none of my usual antidotes could purge it. The only remedy was a rare plant that grew in the heart of a nearby cave, which meant completing an entire dungeon while suffering poison damage with each step. Early in the game, the task would have been impossible—there was just no way to keep up with the damage. But at this late stage of the adventure, with the strongest HP-recovery spell in tow, a whole game’s worth of tools for getting around more safely and easily, and a liberal practice of running away, I was able to secure my panacea before my condition did me in. Scraping by under the pressure of constant, unavoidable damage, in the game’s final chapter prompted one final reevaluation before the finale: have I finally grown strong enough that I don’t need specific remedies for poison? The answer is probably not, but as always, the value of the question is in the process of reflection, not the outcome. Following this episode, I went into the final dungeon with Toxios in hand, just like I always did, but not before looking back at how far I had come since my Poison Balm days.

Footnote

As much as I loved its treatment of poison, Sword of Vermilion is an imperfect exemplar. My run had the quirk that I went through most of it under the mistaken belief that I only had 6 spellbook slots, when in fact I had 8. Predictably, this made choosing spells a much tenser experience. With 8 slots, I can carry Toxios, all four utility spells, the strongest available healing spell, and my favorite attack magic, and still have a slot leftover. With 6 slots, something’s gotta go. With 8, Toxios sees a lot less competition for its spot, and becomes that much more attractive because of it. I don’t think knowing I had 8 slots would have taken the Poison Shield out of the running, but it seems unlikely that I ever would have sold Toxios knowing I had all that space to spare. This is all to say that I’m basing my analysis on an idiosyncratic experience that probably is “unrepresentative” of anyone else’s experiences with the game. Of course, game experiences are always idiosyncratic to a player’s individual habits and perspectives, so I would hesitate to draw broad conclusions even if I had had a more “representative” experience. I believe my observations survive either way (if I didn’t, how would I write anything?), but I would still feel dishonest if I didn’t disclose that the very excellent and inspiring time I had was partially informed by a misunderstanding that resulted in deeper engagement.